Athelstan (or Æthelstan) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Historians regard him as the first King of England and one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings. He never married and was succeeded by his half-brother, Edmund.

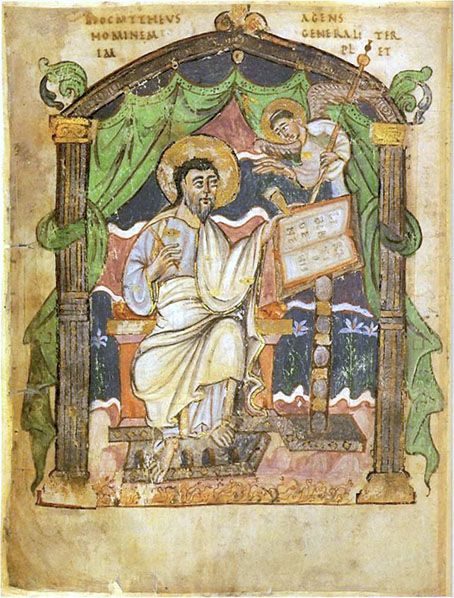

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, an illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert, probaby presented to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street by Æthelstan when he visited the shrine on his journey to Scotland in 934

When Edward died in July 924, Æthelstan was accepted by the Mercians as king. His half-brother Ælfweard may have been recognised as king in Wessex, but died within weeks of their father. Æthelstan still encountered resistance in Wessex for several months, and was not crowned until September 925. In 927 he conquered the last remaining Viking kingdom, York, making him the first Anglo-Saxon ruler of the whole of England. In 934 he invaded Scotland and forced King Constantine of Scotland to submit to him, but Æthelstan's rule was resented by the Scots and Vikings, and in 937 they invaded England. Æthelstan defeated them at the Battle of Brunanburh, a victory which gave him great prestige both in the British Isles and on the Continent. After his death in 939 the Vikings seized back control of York, and it was not finally reconquered until 954.

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, an illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert, probaby presented to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street by Æthelstan when he visited the shrine on his journey to Scotland in 934

When Edward died in July 924, Æthelstan was accepted by the Mercians as king. His half-brother Ælfweard may have been recognised as king in Wessex, but died within weeks of their father. Æthelstan still encountered resistance in Wessex for several months, and was not crowned until September 925. In 927 he conquered the last remaining Viking kingdom, York, making him the first Anglo-Saxon ruler of the whole of England. In 934 he invaded Scotland and forced King Constantine of Scotland to submit to him, but Æthelstan's rule was resented by the Scots and Vikings, and in 937 they invaded England. Æthelstan defeated them at the Battle of Brunanburh, a victory which gave him great prestige both in the British Isles and on the Continent. After his death in 939 the Vikings seized back control of York, and it was not finally reconquered until 954.

Æthelstan centralised government; he increased control over the production of charters and summoned leading figures from distant areas to his councils. These meetings were also attended by rulers from outside his territory, especially Welsh kings, who thus acknowledged his overlordship. More legal texts survive from his reign than from any other tenth-century English king. They show his concern about widespread robberies, and the threat they posed to social order. His legal reforms built on those of his grandfather, Alfred the Great. Æthelstan was one of the most pious West Saxon kings, and was known for collecting relics and founding churches. His household was the centre of English learning during his reign, and it laid the foundation for the Benedictine monastic reform later in the century. No other West Saxon king played as important a role in European politics as Æthelstan, and he arranged the marriages of several of his sisters to continental rulers.

Early Life

According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan was thirty years old when he came to the throne in 924, which would mean that he was born in about 894. He was the oldest son of Edward the Elder, and Edward's only son by his first consort, Ecgwynn. Very little is known about Ecgwynn, and she is not named in any pre-Conquest source. Medieval chroniclers gave varying descriptions of her rank: one described her as an ignoble consort of inferior birth, while others described her birth as noble. Modern historians also disagree about her status. Simon Keynes and Richard Abels believe that leading figures in Wessex were unwilling to accept Æthelstan as king in 924 partly because his mother had been Edward the Elder's concubine. However, Barbara Yorke and Sarah Foot argue that allegations that Æthelstan was illegitimate were a product of the dispute over the succession, and that there is no reason to doubt that she was Edward's legitimate wife. She may have been related to St Dunstan.

William of Malmesbury wrote that Alfred the Great honoured his young grandson with a ceremony in which he gave him a scarlet cloak, a belt set with gems, and a sword with a gilded scabbard. Medieval Latin scholar Michael Lapidge and historian Michael Wood see this as designating Æthelstan as a potential heir at a time when the claim of Alfred's nephew, Æthelwold, to the throne represented a threat to the succession of Alfred's direct line but historian Janet Nelson suggests that it should be seen in the context of conflict between Alfred and Edward in the 890s, and might reflect an intention to divide the realm between his son and his grandson after his death. Historian Martin Ryan goes further, suggesting that at the end of his life Alfred may have favoured Æthelstan rather than Edward as his successor. An acrostic poem praising prince "Adalstan", and prophesying a great future for him, has been interpreted by Lapidge as referring to the young Æthelstan, punning on the old English meaning of his name, "noble stone". Lapidge and Wood see the poem as a commemoration of Alfred's ceremony by one of his leading scholars, John the Old Saxon. In Michael Wood's view, the poem confirms the truth of William of Malmesbury's account of the ceremony. Wood also suggests that Æthelstan may have been the first English king to be groomed from childhood as an intellectual, and that John was probably his tutor. However, Sarah Foot argues that the acrostic poem makes better sense if it is dated to the beginning of Æthelstan's reign.

Æthelstan in a fifteenth-century stained glass window in All Souls College Chapel, Oxford

Edward married his second wife Ælfflæd at about the time of his father's death, probably because Ecgwynn had died, although she may have been put aside. The new marriage weakened Æthelstan's position, as his step-mother naturally favoured the interests of her own sons, Ælfweard and Edwin. By 920 Edward had taken a third wife, Eadgifu, probably after putting Ælfflæd aside. Eadgifu also had two sons, the future kings Edmund and Eadred. Edward had a large number of daughters, perhaps as many as nine.

Æthelstan in a fifteenth-century stained glass window in All Souls College Chapel, Oxford

Edward married his second wife Ælfflæd at about the time of his father's death, probably because Ecgwynn had died, although she may have been put aside. The new marriage weakened Æthelstan's position, as his step-mother naturally favoured the interests of her own sons, Ælfweard and Edwin. By 920 Edward had taken a third wife, Eadgifu, probably after putting Ælfflæd aside. Eadgifu also had two sons, the future kings Edmund and Eadred. Edward had a large number of daughters, perhaps as many as nine.

Æthelstan's later education was probably at the Mercian court of his aunt and uncle, Æthelflæd and Æthelred, and it is likely that the young prince gained his military training in the Mercian campaigns to conquer the Danelaw. According to a transcript dating from 1304, in 925 Æthelstan gave a charter of privileges to St Oswald's Priory, Gloucester, where his aunt and uncle were buried, "according to a pact of paternal piety which he formerly pledged with Æthelred, ealdorman of the people of the Mercians". When Edward took direct control of Mercia after Æthelflæd's death in 918, Æthelstan may have represented his father's interests there.

The Reign of Athelstan

The Struggle for Power: Edward died at Farndon in northern Mercia on 17 July 924, and the ensuing events are unclear. Ælfweard, Edward's eldest son by Ælfflæd, had ranked above Æthelstan in attesting a charter in 901, and Edward may have intended Ælfweard to be his successor as king, either of Wessex only or of the whole kingdom. If Edward had intended his realms to be divided after his death, his deposition of Ælfwynn in Mercia in 918 may have been intended to prepare the way for Æthelstan's succession as king of Mercia. When Edward died, Æthelstan was apparently with him in Mercia, while Ælfweard was in Wessex. Mercia acknowledged Æthelstan as king, and Wessex may have chosen Ælfweard. However, Ælfweard outlived his father by only sixteen days, disrupting any succession plan.

Even after Ælfweard's death there seems to have been opposition to Æthelstan in Wessex, particularly in Winchester, where Ælfweard was buried. At first Æthelstan behaved as a Mercian king. A charter relating to land in Derbyshire, which appears to have been issued at a time in 925 when his authority had not yet been recognised outside Mercia, was witnessed only by Mercian bishops. In the view of historians David Dumville and Janet Nelson he may have agreed not to marry or have heirs in order to gain acceptance. However, Sarah Foot ascribes his decision to remain unmarried to "a religiously motivated determination on chastity as a way of life".

The coronation of Æthelstan took place on 4 September 925 at Kingston upon Thames, perhaps due to its symbolic location on the border between Wessex and Mercia He was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Athelm, who probably designed or organised a new ordo (religious order of service) in which the king wore a crown for the first time instead of a helmet. The new ordo was influenced by West Frankish liturgy and in turn became one of the sources of the medieval French ordo.

Opposition seems to have continued even after the coronation. According to William of Malmesbury, an otherwise unknown nobleman called Alfred plotted to blind Æthelstan on account of his supposed illegitimacy, although it is unknown whether he aimed to make himself king or was acting on behalf of Edwin, Ælfweard's younger brother. Blinding would have been a sufficient disability to render Æthelstan ineligible for kingship without incurring the odium attached to murder. Tensions between Æthelstan and Winchester seem to have continued for some years. The Bishop of Winchester, Frithestan, did not attend the coronation or witness any of Æthelstan's known charters until 928. After that he witnessed fairly regularly until his resignation in 931, but was listed in a lower position than entitled by his seniority.

In 933 Edwin was drowned in a shipwreck in the North Sea. His cousin, Adelolf, Count of Boulogne, took his body for burial at St Bertin Abbey in Saint-Omer. According to the abbey's annalist, Folcuin, who wrongly believed that Edwin had been king, he had fled England "driven by some disturbance in his kingdom". Folcuin stated that Æthelstan sent alms to the abbey for his dead brother and received monks from the abbey graciously when they came to England, although Folcuin did not realise that Æthelstan died before the monks made the journey in 944. The twelfth-century chronicler Symeon of Durham said that Æthelstan ordered Edwin to be drowned, but this is generally dismissed by historians. Edwin may have fled England after an unsuccessful rebellion against his brother's rule, and his death probably helped put an end to Winchester's opposition.

King of all England: Edward the Elder had conquered the Danish territories in Mercia and East Anglia with the assistance of Æthelflæd and her husband, but when Edward died the Danish king Sihtric still ruled the Viking Kingdom of York (formerly the southern Northumbrian kingdom of Deira). In January 926, Æthelstan arranged for one of his sisters to marry Sihtric. The two kings agreed not to invade each other's territories or to support each other's enemies. The following year Sihtric died, and Æthelstan seized the chance to invade. Guthfrith, a cousin of Sihtric, led a fleet from Dublin to try to take the throne, but Æthelstan easily prevailed. He captured York and received the submission of the Danish people. According to a southern chronicler, he "succeeded to the kingdom of the Northumbrians", and it is uncertain whether he had to fight Guthfrith. Southern kings had never ruled the north, and his usurpation was met with outrage by the Northumbrians, who had always resisted southern control. However, at Eamont, near Penrith, on 12 July 927, King Constantine of Scotland, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Ealdred of Bamburgh, and King Owain of Strathclyde (or Morgan ap Owain of Gwent) accepted Æthelstan's overlordship. His triumph led to seven years of peace in the north.

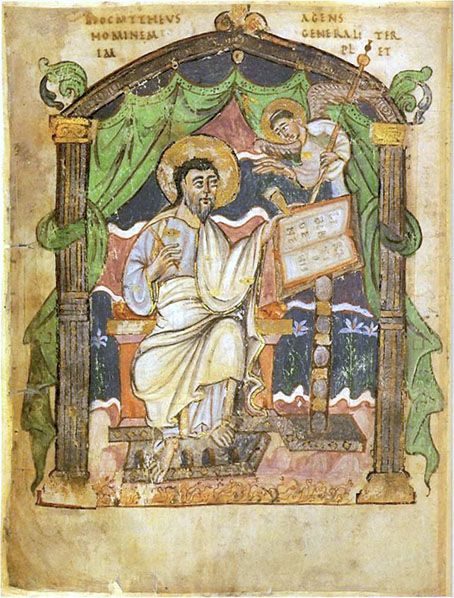

Miniature of St Matthew in the Carolingian gospels presented by Æthelstan to Christ Church Priory, Canterbury

Whereas Æthelstan was the first English king to achieve lordship over northern Britain, he inherited his authority over the Welsh kings from his father and aunt. In the 910s Gwent acknowledged the lordship of Wessex, and Deheubarth and Gwynedd accepted that of Æthelflæd of Mercia; following Edward's takeover of Mercia, they transferred their allegiance to him. According to William of Malmesbury, after the meeting at Eamont Æthelstan summoned the Welsh kings to Hereford, where he imposed a heavy annual tribute and fixed the border between England and Wales in the Hereford area at the River Wye. The dominant figure in Wales was Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, described by the historian of early medieval Wales Thomas Charles-Edwards as "the firmest ally of the 'emperors of Britain' among all the kings of his day". Welsh kings attended Æthelstan's court between 928 and 935 and witnessed charters at the head of the list of laity (apart from the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde), showing that their position was regarded as superior to that of the other great men present. The alliance produced peace between Wales and England, and within Wales, lasting throughout Æthelstan's reign, though some Welsh resented the status of their rulers as sub-kings, as well as the high level of tribute imposed upon them. In Armes Prydein Vawr (The Great Prophecy of Britain), a Welsh poet foresaw the day when the British would rise up against their Saxon oppressors and drive them into the sea.

Miniature of St Matthew in the Carolingian gospels presented by Æthelstan to Christ Church Priory, Canterbury

Whereas Æthelstan was the first English king to achieve lordship over northern Britain, he inherited his authority over the Welsh kings from his father and aunt. In the 910s Gwent acknowledged the lordship of Wessex, and Deheubarth and Gwynedd accepted that of Æthelflæd of Mercia; following Edward's takeover of Mercia, they transferred their allegiance to him. According to William of Malmesbury, after the meeting at Eamont Æthelstan summoned the Welsh kings to Hereford, where he imposed a heavy annual tribute and fixed the border between England and Wales in the Hereford area at the River Wye. The dominant figure in Wales was Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, described by the historian of early medieval Wales Thomas Charles-Edwards as "the firmest ally of the 'emperors of Britain' among all the kings of his day". Welsh kings attended Æthelstan's court between 928 and 935 and witnessed charters at the head of the list of laity (apart from the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde), showing that their position was regarded as superior to that of the other great men present. The alliance produced peace between Wales and England, and within Wales, lasting throughout Æthelstan's reign, though some Welsh resented the status of their rulers as sub-kings, as well as the high level of tribute imposed upon them. In Armes Prydein Vawr (The Great Prophecy of Britain), a Welsh poet foresaw the day when the British would rise up against their Saxon oppressors and drive them into the sea.

According to William of Malmesbury, after the Hereford meeting Æthelstan went on to expel the Cornish from Exeter, fortify its walls, and fix the Cornish boundary at the River Tamar. This account is regarded sceptically by historians, however, as Cornwall had been under English rule since the mid-ninth century. Thomas Charles-Edwards describes it as "an improbable story", while historian John Reuben Davies sees it as the suppression of a British revolt and the confinement of the Cornish beyond the Tamar. Æthelstan emphasised his control by establishing a new Cornish see and appointing its first bishop, but Cornwall kept its own culture and language.

Æthelstan became the first king of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, and in effect over-king of Britain. His successes inaugurated what John Maddicott, in his history of the origins of the English Parliament, calls the imperial phase of English kingship between about 925 and 975, when rulers from Wales and Scotland attended the assemblies of English kings and witnessed their charters. Æthelstan tried to reconcile the aristocracy in his new territory of Northumbria to his rule. He lavished gifts on the minsters of Beverley, Chester-le-Street, and York, emphasising his Christianity. He also purchased the vast territory of Amounderness in Lancashire, and gave it to the Archbishop of York, his most important lieutenant in the region. But he remained a resented outsider, and the northern British kingdoms preferred to ally with the pagan Norse of Dublin. In contrast to his strong control over southern Britain, his position in the north was far more tenuous.

The invasion of Scotland in 934: In 934 Æthelstan invaded Scotland. His reasons are unclear, and historians give alternative explanations. The death of his half-brother Edwin in 933 may have finally removed factions in Wessex opposed to his rule. Guthfrith, the Norse king of Dublin who had briefly ruled Northumbria, died in 934; any resulting insecurity among the Danes may have given Æthelstan an opportunity to stamp his authority on the north. An entry in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, recording the death in 934 of a ruler who may have been Ealdred of Bamburgh, suggests another possible explanation. This may have led to a dispute between Æthelstan and Constantine over control of his territory. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle briefly recorded the expedition without explanation, but the twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester stated that Constantine had broken his treaty with Æthelstan.

Æthelstan set out on his campaign in May 934, accompanied by four Welsh kings: Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Idwal Foel of Gwynedd, Morgan ap Owain of Gwent, and Tewdwr ap Griffri of Brycheiniog. His retinue also included eighteen bishops and thirteen earls, six of whom were Danes from eastern England. By late June or early July he had reached Chester-le-Street, where he made generous gifts to the tomb of St Cuthbert, including a stole and maniple (ecclesiastical garments) originally commissioned by his step-mother Ælfflæd as a gift to Bishop Frithestan of Winchester. The invasion was launched by land and sea. According to the twelfth-century chronicler Simeon of Durham, his land forces ravaged as far as Dunnottar in north-east Scotland, while the fleet raided Caithness, then probably part of the Norse kingdom of Orkney.

No battles are recorded during the campaign, and chronicles do not record its outcome. By September, however, he was back in the south of England at Buckingham, where Constantine witnessed a charter as subregulus, that is a king acknowledging Æthelstan's overlordship. In 935 a charter was attested by Constantine, Owain of Strathclyde, Hywel Dda, Idwal Foel, and Morgan ap Owain. At Christmas of the same year Owain of Strathclyde was once more at Æthelstan's court along with the Welsh kings, but Constantine was not. His return to England less than two years later would be in very different circumstances.

The Battle of Brunanburh: In 934 Olaf Guthfrithson succeeded his father Guthfrith as the Norse King of Dublin. The alliance between the Norse and the Scots was cemented by the marriage of Olaf to Constantine's daughter. By August 937 Olaf had defeated his rivals for control of the Viking part of Ireland, and he promptly launched a bid for the former Norse kingdom of York.

Individually Olaf and Constantine were too weak to oppose Æthelstan, but together they could hope to challenge the dominance of Wessex. In the autumn they joined with the Strathclyde Britons under Owain to invade England. Medieval campaigning was normally conducted in the summer, and Æthelstan can hardly have expected an invasion on such a large scale so late in the year. He seems to have been slow to react, and an old Latin poem preserved by William of Malmesbury accused him of having "languished in sluggish leisure". The allies plundered the north-west while Æthelstan took his time gathering a West Saxon and Mercian army. However, Michael Wood praises his caution, arguing that unlike Harold in 1066, he did not allow himself to be provoked into precipitate action. When he marched north, the Welsh did not join him, and they did not fight on either side.

The two sides met at the Battle of Brunanburh, resulting in an overwhelming victory for Æthelstan, supported by his young half-brother, the future King Edmund I. Olaf escaped back to Dublin with the remnant of his forces, while Constantine lost a son. The English also suffered heavy losses, including two of Æthelstan's cousins, sons of Edward the Elder's younger brother, Æthelweard.

The battle was reported in the Annals of Ulster thus:

A great, lamentable and horrible battle was cruelly fought between the Saxons and the Northmen, in which several thousands of Northmen, who are uncounted, fell, but their king Amlaib [Olaf], escaped with a few followers. A large number of Saxons fell on the other side, but Æthelstan, king of the Saxons, enjoyed a great victory.

A generation later, the chronicler Æthelweard reported that it was popularly remembered as "the great battle", and it sealed Æthelstan's posthumous reputation as "victorious because of God" (in the words of the homilist Ælfric of Eynsham). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle abandoned its usual terse style in favour of a heroic poem vaunting the great victory, employing imperial language to present Æthelstan as ruler of an empire of Britain. The site of the battle is uncertain, however, and over thirty sites have been suggested, with Bromborough on the Wirral the most favoured among historians.

Historians disagree over the significance of the battle. Alex Woolf describes it as a pyrrhic victory for Æthelstan: the campaign seems to have ended in a stalemate, his power appears to have declined and after he died Olaf acceded to the kingdom of Northumbria without resistance. Alfred Smyth describes it as "the greatest battle in Anglo-Saxon history", but he also states that its consequences beyond Æthelstan's reign have been overstated. In the view of Sarah Foot, on the other hand, it would be difficult to exaggerate the battle's importance: if the Anglo-Saxons had been defeated, their hegemony over the whole mainland of Britain would have disintegrated.

Athelstan's Death

Æthelstan died at Gloucester on 27 October 939. His grandfather Alfred, his father Edward, and his half-brother Ælfweard had been buried at Winchester, but Æthelstan chose not to honour the city associated with opposition to his rule. By his own wish he was buried at Malmesbury Abbey, where he had buried his cousins who died at Brunanburh. No other member of the West Saxon royal family was buried there, and according to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan's choice reflected his devotion to the abbey and to the memory of its seventh-century abbot, Saint Aldhelm. William described Æthelstan as fair-haired "as I have seen for myself in his remains, beautifully intertwined with gold threads". His bones were lost during the Reformation, but he is commemorated by an empty fifteenth-century tomb.

Taken from Wikipedia.

To download this history as a pdf file click here

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, an illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert, probaby presented to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street by Æthelstan when he visited the shrine on his journey to Scotland in 934

Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, an illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert, probaby presented to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street by Æthelstan when he visited the shrine on his journey to Scotland in 934Æthelstan centralised government; he increased control over the production of charters and summoned leading figures from distant areas to his councils. These meetings were also attended by rulers from outside his territory, especially Welsh kings, who thus acknowledged his overlordship. More legal texts survive from his reign than from any other tenth-century English king. They show his concern about widespread robberies, and the threat they posed to social order. His legal reforms built on those of his grandfather, Alfred the Great. Æthelstan was one of the most pious West Saxon kings, and was known for collecting relics and founding churches. His household was the centre of English learning during his reign, and it laid the foundation for the Benedictine monastic reform later in the century. No other West Saxon king played as important a role in European politics as Æthelstan, and he arranged the marriages of several of his sisters to continental rulers.

Early Life

According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan was thirty years old when he came to the throne in 924, which would mean that he was born in about 894. He was the oldest son of Edward the Elder, and Edward's only son by his first consort, Ecgwynn. Very little is known about Ecgwynn, and she is not named in any pre-Conquest source. Medieval chroniclers gave varying descriptions of her rank: one described her as an ignoble consort of inferior birth, while others described her birth as noble. Modern historians also disagree about her status. Simon Keynes and Richard Abels believe that leading figures in Wessex were unwilling to accept Æthelstan as king in 924 partly because his mother had been Edward the Elder's concubine. However, Barbara Yorke and Sarah Foot argue that allegations that Æthelstan was illegitimate were a product of the dispute over the succession, and that there is no reason to doubt that she was Edward's legitimate wife. She may have been related to St Dunstan.

William of Malmesbury wrote that Alfred the Great honoured his young grandson with a ceremony in which he gave him a scarlet cloak, a belt set with gems, and a sword with a gilded scabbard. Medieval Latin scholar Michael Lapidge and historian Michael Wood see this as designating Æthelstan as a potential heir at a time when the claim of Alfred's nephew, Æthelwold, to the throne represented a threat to the succession of Alfred's direct line but historian Janet Nelson suggests that it should be seen in the context of conflict between Alfred and Edward in the 890s, and might reflect an intention to divide the realm between his son and his grandson after his death. Historian Martin Ryan goes further, suggesting that at the end of his life Alfred may have favoured Æthelstan rather than Edward as his successor. An acrostic poem praising prince "Adalstan", and prophesying a great future for him, has been interpreted by Lapidge as referring to the young Æthelstan, punning on the old English meaning of his name, "noble stone". Lapidge and Wood see the poem as a commemoration of Alfred's ceremony by one of his leading scholars, John the Old Saxon. In Michael Wood's view, the poem confirms the truth of William of Malmesbury's account of the ceremony. Wood also suggests that Æthelstan may have been the first English king to be groomed from childhood as an intellectual, and that John was probably his tutor. However, Sarah Foot argues that the acrostic poem makes better sense if it is dated to the beginning of Æthelstan's reign.

Æthelstan in a fifteenth-century stained glass window in All Souls College Chapel, Oxford

Æthelstan in a fifteenth-century stained glass window in All Souls College Chapel, OxfordÆthelstan's later education was probably at the Mercian court of his aunt and uncle, Æthelflæd and Æthelred, and it is likely that the young prince gained his military training in the Mercian campaigns to conquer the Danelaw. According to a transcript dating from 1304, in 925 Æthelstan gave a charter of privileges to St Oswald's Priory, Gloucester, where his aunt and uncle were buried, "according to a pact of paternal piety which he formerly pledged with Æthelred, ealdorman of the people of the Mercians". When Edward took direct control of Mercia after Æthelflæd's death in 918, Æthelstan may have represented his father's interests there.

The Reign of Athelstan

The Struggle for Power: Edward died at Farndon in northern Mercia on 17 July 924, and the ensuing events are unclear. Ælfweard, Edward's eldest son by Ælfflæd, had ranked above Æthelstan in attesting a charter in 901, and Edward may have intended Ælfweard to be his successor as king, either of Wessex only or of the whole kingdom. If Edward had intended his realms to be divided after his death, his deposition of Ælfwynn in Mercia in 918 may have been intended to prepare the way for Æthelstan's succession as king of Mercia. When Edward died, Æthelstan was apparently with him in Mercia, while Ælfweard was in Wessex. Mercia acknowledged Æthelstan as king, and Wessex may have chosen Ælfweard. However, Ælfweard outlived his father by only sixteen days, disrupting any succession plan.

Even after Ælfweard's death there seems to have been opposition to Æthelstan in Wessex, particularly in Winchester, where Ælfweard was buried. At first Æthelstan behaved as a Mercian king. A charter relating to land in Derbyshire, which appears to have been issued at a time in 925 when his authority had not yet been recognised outside Mercia, was witnessed only by Mercian bishops. In the view of historians David Dumville and Janet Nelson he may have agreed not to marry or have heirs in order to gain acceptance. However, Sarah Foot ascribes his decision to remain unmarried to "a religiously motivated determination on chastity as a way of life".

The coronation of Æthelstan took place on 4 September 925 at Kingston upon Thames, perhaps due to its symbolic location on the border between Wessex and Mercia He was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Athelm, who probably designed or organised a new ordo (religious order of service) in which the king wore a crown for the first time instead of a helmet. The new ordo was influenced by West Frankish liturgy and in turn became one of the sources of the medieval French ordo.

Opposition seems to have continued even after the coronation. According to William of Malmesbury, an otherwise unknown nobleman called Alfred plotted to blind Æthelstan on account of his supposed illegitimacy, although it is unknown whether he aimed to make himself king or was acting on behalf of Edwin, Ælfweard's younger brother. Blinding would have been a sufficient disability to render Æthelstan ineligible for kingship without incurring the odium attached to murder. Tensions between Æthelstan and Winchester seem to have continued for some years. The Bishop of Winchester, Frithestan, did not attend the coronation or witness any of Æthelstan's known charters until 928. After that he witnessed fairly regularly until his resignation in 931, but was listed in a lower position than entitled by his seniority.

In 933 Edwin was drowned in a shipwreck in the North Sea. His cousin, Adelolf, Count of Boulogne, took his body for burial at St Bertin Abbey in Saint-Omer. According to the abbey's annalist, Folcuin, who wrongly believed that Edwin had been king, he had fled England "driven by some disturbance in his kingdom". Folcuin stated that Æthelstan sent alms to the abbey for his dead brother and received monks from the abbey graciously when they came to England, although Folcuin did not realise that Æthelstan died before the monks made the journey in 944. The twelfth-century chronicler Symeon of Durham said that Æthelstan ordered Edwin to be drowned, but this is generally dismissed by historians. Edwin may have fled England after an unsuccessful rebellion against his brother's rule, and his death probably helped put an end to Winchester's opposition.

King of all England: Edward the Elder had conquered the Danish territories in Mercia and East Anglia with the assistance of Æthelflæd and her husband, but when Edward died the Danish king Sihtric still ruled the Viking Kingdom of York (formerly the southern Northumbrian kingdom of Deira). In January 926, Æthelstan arranged for one of his sisters to marry Sihtric. The two kings agreed not to invade each other's territories or to support each other's enemies. The following year Sihtric died, and Æthelstan seized the chance to invade. Guthfrith, a cousin of Sihtric, led a fleet from Dublin to try to take the throne, but Æthelstan easily prevailed. He captured York and received the submission of the Danish people. According to a southern chronicler, he "succeeded to the kingdom of the Northumbrians", and it is uncertain whether he had to fight Guthfrith. Southern kings had never ruled the north, and his usurpation was met with outrage by the Northumbrians, who had always resisted southern control. However, at Eamont, near Penrith, on 12 July 927, King Constantine of Scotland, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Ealdred of Bamburgh, and King Owain of Strathclyde (or Morgan ap Owain of Gwent) accepted Æthelstan's overlordship. His triumph led to seven years of peace in the north.

Miniature of St Matthew in the Carolingian gospels presented by Æthelstan to Christ Church Priory, Canterbury

Miniature of St Matthew in the Carolingian gospels presented by Æthelstan to Christ Church Priory, CanterburyAccording to William of Malmesbury, after the Hereford meeting Æthelstan went on to expel the Cornish from Exeter, fortify its walls, and fix the Cornish boundary at the River Tamar. This account is regarded sceptically by historians, however, as Cornwall had been under English rule since the mid-ninth century. Thomas Charles-Edwards describes it as "an improbable story", while historian John Reuben Davies sees it as the suppression of a British revolt and the confinement of the Cornish beyond the Tamar. Æthelstan emphasised his control by establishing a new Cornish see and appointing its first bishop, but Cornwall kept its own culture and language.

Æthelstan became the first king of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, and in effect over-king of Britain. His successes inaugurated what John Maddicott, in his history of the origins of the English Parliament, calls the imperial phase of English kingship between about 925 and 975, when rulers from Wales and Scotland attended the assemblies of English kings and witnessed their charters. Æthelstan tried to reconcile the aristocracy in his new territory of Northumbria to his rule. He lavished gifts on the minsters of Beverley, Chester-le-Street, and York, emphasising his Christianity. He also purchased the vast territory of Amounderness in Lancashire, and gave it to the Archbishop of York, his most important lieutenant in the region. But he remained a resented outsider, and the northern British kingdoms preferred to ally with the pagan Norse of Dublin. In contrast to his strong control over southern Britain, his position in the north was far more tenuous.

The invasion of Scotland in 934: In 934 Æthelstan invaded Scotland. His reasons are unclear, and historians give alternative explanations. The death of his half-brother Edwin in 933 may have finally removed factions in Wessex opposed to his rule. Guthfrith, the Norse king of Dublin who had briefly ruled Northumbria, died in 934; any resulting insecurity among the Danes may have given Æthelstan an opportunity to stamp his authority on the north. An entry in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, recording the death in 934 of a ruler who may have been Ealdred of Bamburgh, suggests another possible explanation. This may have led to a dispute between Æthelstan and Constantine over control of his territory. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle briefly recorded the expedition without explanation, but the twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester stated that Constantine had broken his treaty with Æthelstan.

Æthelstan set out on his campaign in May 934, accompanied by four Welsh kings: Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Idwal Foel of Gwynedd, Morgan ap Owain of Gwent, and Tewdwr ap Griffri of Brycheiniog. His retinue also included eighteen bishops and thirteen earls, six of whom were Danes from eastern England. By late June or early July he had reached Chester-le-Street, where he made generous gifts to the tomb of St Cuthbert, including a stole and maniple (ecclesiastical garments) originally commissioned by his step-mother Ælfflæd as a gift to Bishop Frithestan of Winchester. The invasion was launched by land and sea. According to the twelfth-century chronicler Simeon of Durham, his land forces ravaged as far as Dunnottar in north-east Scotland, while the fleet raided Caithness, then probably part of the Norse kingdom of Orkney.

No battles are recorded during the campaign, and chronicles do not record its outcome. By September, however, he was back in the south of England at Buckingham, where Constantine witnessed a charter as subregulus, that is a king acknowledging Æthelstan's overlordship. In 935 a charter was attested by Constantine, Owain of Strathclyde, Hywel Dda, Idwal Foel, and Morgan ap Owain. At Christmas of the same year Owain of Strathclyde was once more at Æthelstan's court along with the Welsh kings, but Constantine was not. His return to England less than two years later would be in very different circumstances.

The Battle of Brunanburh: In 934 Olaf Guthfrithson succeeded his father Guthfrith as the Norse King of Dublin. The alliance between the Norse and the Scots was cemented by the marriage of Olaf to Constantine's daughter. By August 937 Olaf had defeated his rivals for control of the Viking part of Ireland, and he promptly launched a bid for the former Norse kingdom of York.

Individually Olaf and Constantine were too weak to oppose Æthelstan, but together they could hope to challenge the dominance of Wessex. In the autumn they joined with the Strathclyde Britons under Owain to invade England. Medieval campaigning was normally conducted in the summer, and Æthelstan can hardly have expected an invasion on such a large scale so late in the year. He seems to have been slow to react, and an old Latin poem preserved by William of Malmesbury accused him of having "languished in sluggish leisure". The allies plundered the north-west while Æthelstan took his time gathering a West Saxon and Mercian army. However, Michael Wood praises his caution, arguing that unlike Harold in 1066, he did not allow himself to be provoked into precipitate action. When he marched north, the Welsh did not join him, and they did not fight on either side.

The two sides met at the Battle of Brunanburh, resulting in an overwhelming victory for Æthelstan, supported by his young half-brother, the future King Edmund I. Olaf escaped back to Dublin with the remnant of his forces, while Constantine lost a son. The English also suffered heavy losses, including two of Æthelstan's cousins, sons of Edward the Elder's younger brother, Æthelweard.

The battle was reported in the Annals of Ulster thus:

A great, lamentable and horrible battle was cruelly fought between the Saxons and the Northmen, in which several thousands of Northmen, who are uncounted, fell, but their king Amlaib [Olaf], escaped with a few followers. A large number of Saxons fell on the other side, but Æthelstan, king of the Saxons, enjoyed a great victory.

A generation later, the chronicler Æthelweard reported that it was popularly remembered as "the great battle", and it sealed Æthelstan's posthumous reputation as "victorious because of God" (in the words of the homilist Ælfric of Eynsham). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle abandoned its usual terse style in favour of a heroic poem vaunting the great victory, employing imperial language to present Æthelstan as ruler of an empire of Britain. The site of the battle is uncertain, however, and over thirty sites have been suggested, with Bromborough on the Wirral the most favoured among historians.

Historians disagree over the significance of the battle. Alex Woolf describes it as a pyrrhic victory for Æthelstan: the campaign seems to have ended in a stalemate, his power appears to have declined and after he died Olaf acceded to the kingdom of Northumbria without resistance. Alfred Smyth describes it as "the greatest battle in Anglo-Saxon history", but he also states that its consequences beyond Æthelstan's reign have been overstated. In the view of Sarah Foot, on the other hand, it would be difficult to exaggerate the battle's importance: if the Anglo-Saxons had been defeated, their hegemony over the whole mainland of Britain would have disintegrated.

Athelstan's Death

Æthelstan died at Gloucester on 27 October 939. His grandfather Alfred, his father Edward, and his half-brother Ælfweard had been buried at Winchester, but Æthelstan chose not to honour the city associated with opposition to his rule. By his own wish he was buried at Malmesbury Abbey, where he had buried his cousins who died at Brunanburh. No other member of the West Saxon royal family was buried there, and according to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan's choice reflected his devotion to the abbey and to the memory of its seventh-century abbot, Saint Aldhelm. William described Æthelstan as fair-haired "as I have seen for myself in his remains, beautifully intertwined with gold threads". His bones were lost during the Reformation, but he is commemorated by an empty fifteenth-century tomb.

Taken from Wikipedia.

To download this history as a pdf file click here